By Hope Dean

The Alligator / University of Florida

When it comes to improving healthcare, the cellphone in your pocket might just be one of the keys to progress — or it could act as a bandage covering the real problem.

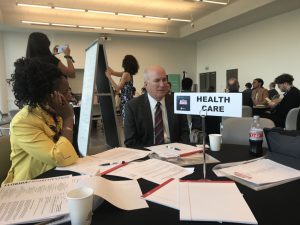

Over 30 businesspeople, education leaders, public administrators and other state influencers met Monday, Nov. 18, at the University of Miami to discuss state issues, including healthcare. Their recommendations will be submitted to the Florida Legislature once the new legislative session begins Jan. 14.

The second-annual Florida Priorities Summit healthcare panel, comprised of five industry leaders involved with hospital care, health insurance and Medicaid, advised that the legislature should focus on establishing video chat or telephone-facilitated healthcare, public service announcements for cheap medicine and medical resource directories instead of medicare.

But experts in Alachua County don’t think these new measures will do much to help those with inadequate or no health insurance in the area.

Victoria Kasdan, panel member and former executive director of free healthcare organization We Care Manatee, believes that focusing on these measures is a more realistic approach due to their lower costs and political pressure.

“It’s easier than trying to get them to pass a law,” she said. “Expand Medicaid? They’re not going to do that, so we’re not even talking about it.”

Grant Harrell, medical director of the University of Florida’s Mobile Outreach Clinic, disagrees about needing to expand Medicaid.

The mobile clinic is a large bus with medical examination rooms and a lab that drives around Alachua County to provide healthcare for free. It serves about 3,000 patients yearly, most of whom suffer from poverty, homelessness or unemployment, Harrell said.

“That’s basically us trying to do our best with the dysfunctional health system that we have. But that’s not a way of solving the problem,” he said. “Minimally augmenting the safety net is not going to be a long-term solution for people without insurance or at a lack of access to care.”

About 8.8 percent of America’s population is uninsured. That number is 9 percent in Alachua County and 12.9 percent statewide, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

The clinic bus is dependent on grants instead of a steady stream of government funds. One grant comes from the Community Health Offering Innovative Care & Educational Services (CHOICES) trust fund, which hands out $465,000 annually to healthcare providers in Alachua County, according to Choices Program Manager Cindy Bishop.

The CHOICES fund — provided by money generated from a Florida sales tax for healthcare needs that was suspended in 2011 — funds 8 agencies and 10 programs that help with healthcare in Alachua County.

Now, there is no source replenishing the fund and it will run out in five or six years, Bishop said.

Alachua County has tried some of the Florida Priorities Summit’s proposed solutions before. UF Professor Laura Guyer, a healthcare professional, spearheaded the Alachua County Community Health and Social Service Resource Guide in 2016. She and her students update the guide annually, she said.

Guyer didn’t expect it to take off the way it did. Copies were circulated throughout the county and two resource-directing apps based on Guyer’s guide are currently being developed by the Gainesville city manager and UF’s Equal Access Clinic Network.

While the guide helps, it isn’t enough to support the uninsured, underinsured or those in rural areas with limited access to clinics, she said.

“Those folks who are so unwilling to examine this issue, I just wonder if they’ve ever had a family member unable to find a dentist or a doctor,” she said. “It’s just cruel to make laws that make it unable for people to access care.

Alachua County is dotted with over 10 specially adapted clinics that provide poor people with more affordable healthcare. However, these clinics are often dependent on grant money that is given on a shaky year-to-year basis.

One recent victim is The Alachua County Organization for Rural Needs (ACORN) Clinic. Guyer, who is also the board’s vice president, said it shut down last month due to grant cuts. It had been open for 45 years.

Guyer wants lawmakers to consider that the solution might be in equity, not equality. A tall person does not need a box to stand on to see over a fence, but a short person will, she said.

“People are born into circumstances that are not under their control, and so they are disadvantaged from the beginning,” Guyer said. “If we can’t change somebody’s economic situation — and that’s tough to do — what can we fix to at least make sure that they can be part of the game?”